It results in a decrease in energy (increase in wavelength) of the photon (which may be an X-ray or gamma ray photon), called the Compton effect. But we've done it and this is the way it comes out.Compton scattering is the elastic scattering of a photon by a quasi-free charged particle, usually an electron. So you got to send in light with a really tiny wavelength, 100 times smaller than an atom in order to get an appreciable Compton scattering effect. So this actually is about 100 times smaller than the atom. So a pecometer is a trillionth of a meter. That Compton wavelength is really really really small. Large compared to what? Small compared to what? Large or small compared to the Compton wavelength of the electron. So that gives us a quantitative explanation of what is meant by what I said earlier, large wavelength it behaves like a wave, small wavelength behaves like a particle. We'll get a large effect if the wavelength is much smaller than the Compton wavelength and we'll get a small effect if the wavelength is much bigger. So the Compton scattering is determined by how big the wavelength of the light that you're sending in is, in comparison to the Compton wavelength. If on the other hand h over mc is very very very large compared to the wavelength of the radiation that you're sending in to hit the electron, then this shift in wavelength is going to be huge.

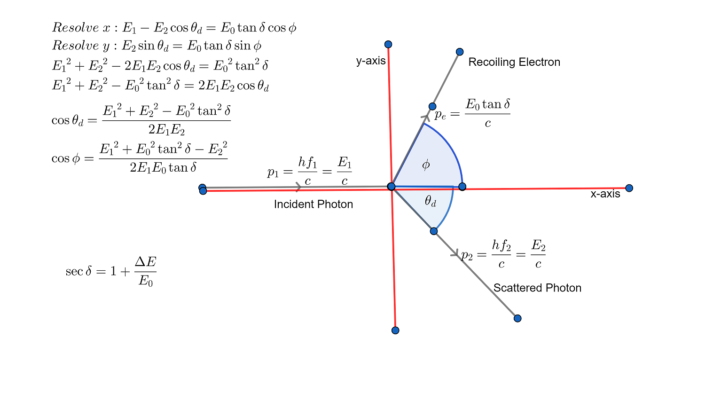

Now, if h over mc is really really really small compared to the wavelength of light, then the shift in wavelength is relatively really small. In fact it does, it's called the Compton wavelength of an electron. So that means that h over mc must play the role of a wavelength. So, what's interesting is that this shift in wavelength is associated with h over mc. So we have a shift in the wavelength which is given by h over mc, m is the mass of the electron, c is the speed of light, h of course is Planck's constant times one minus the cosine of the angle that the photon went off at, alright. He's behaving like a particle and he's just going to change his energy and whenever that requires of the wavelength where it's going to change. So that means that the outgoing photon has a different wavelength than the incoming one. The answer tells us that in order to conserve energy and momentum, I've got to have a shift in the wavelength. Now when you go through this energy momentum process which I'm not going to do on the board for you right now because it is kind of complicated. We can also write this as the energy divided by the speed of light in the vacuum. Planck's constant divided by the wavelength of the radiation. We also know and this actually kind of came from Compton scattering, that the momentum of the photon is given by h over lambda. Well we know form the blackbody radiation spectrum and also from the photoelectric effect that the energy associated with the photon is h times the frequency. We've got to know what the energy of the photon is and what its momentum is. So when we go through and we want to conserve energy and momentum, well jeez. So we're not having any inelastic, it's not like you can deform the electron. This is going to be an elastic collision because afterwards, what have we got? Well, we got an electron and we got a photon. We go through and we conserve energy and we conserve momentum. So, we've got this collision and we're going to do the, exactly the same thing that we always do with every collision between two particles. So let's see what else happens in this process. As long as it's got a small enough wavelength to really behave like a particle. And that's what happens when we have light incident on an electron. Light comes in, hits the electron and then they go off at different angles. And so we actually get a collision like this. So here we've got photons and when you take a particle and you throw it at another particle, this particle is not going to go like that.

However, when the light has a very small wavelength it behaves like a particle.

So if you send the light into a metal where the electrons can go back and forth, the electrons are just going to go up and down and up and down and up and down with the electric field associated with that electromagnetic wave. When light has a very very very large wavelength, it behaves like a wave. They really, like really does behave like a particle, sometimes. Compton scattering is another one of those really important events that happened at the beginning of the 20th century that indicated that photons were real.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)